Published in the Jerusalem Post, 30 June 2025

In any consideration of a possible regime change in Iran, one potential leader stands symbolically head and shoulders above anyone else – the man born to be Shah of Iran and who, for the first nineteen years of his life, was its Crown Prince, namely Reza Pahlavi, now 65 years old.

When his father, faced by an army

mutiny and violent public demonstrations, went into voluntary exile on January

17, 1979 young Pahlavi was a trainee fighter pilot at a US air base in

Texas. Two weeks later Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the spiritual leader

of the Islamic revolution, took control of the country. Neither Pahlavi

nor his father ever set foot in Iran again.

To end his own exile has been

Pahlavi’s main purpose in life for the past 46 years. Though living in the West

under the constant threat of assassination, he has campaigned constantly for

the overthrow of the rule of the ayatollahs and to return home to help create a

new modern, liberal democracy that respects human rights, freedom and

equality.

In pursuit of his aim he leads a

body called the National Council of Iran for Free Elections

(NCI). The Council, an umbrella group of exiled opposition

figures, seeks to restore Pahlavi to the leadership of Iran, either as Shah or

as president. Meanwhile it acts as a government-in-exile, and claims

to have gathered "tens of thousands of pro-democracy proponents from both

inside and outside Iran."

On June 23, in a press conference

held in Paris, Pahlavi called for an end of Iran’s theocratic government.

In its place he proposed establishing a constitution based on the separation of

religion and state, with liberty and equality for all citizens.

“I am stepping forward to lead

this national transition,” he said, “not out of personal interests, but as a

servant of the Iranian people.” Promising a national referendum on the

nature of a future democratic Iran, he called on the “patriotic members of our

armed forces” to “join the people”.

Pahlavi is not intent on

masterminding either a military or a popular coup. He appears to believe

that a spontaneous popular uprising will topple the regime. His starting

point is the burgeoning disillusion with the regime among the Iranian people.

When Iran’s then-incumbent president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, was declared the winner of the presidential election in 2009 with 63% of the vote, the Iranian public was outraged. The whole tenor of the campaign had suggested he was about to be ousted by a large majority. Two of the other candidates, Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, alleged widespread electoral fraud and vote rigging, and called on the Iranian people to protest.

The mass demonstrations that broke

out across the country gave rise to what became known as the Green Movement, a

symbol of unity and hope for those demanding political reform.

The crackdown by the IRGC (Islamic

Revolutionary Guard Corps),was brutal. Thousands were detained, while

reports emerged of severe abuse, torture, and even deaths in detention.

Some protesters were killed in the streets. Dozens of detained protesters and

reformists were paraded in televised trials to intimidate dissenters.

That is what might be expected

following any attempt at regime change in Iran that was less than meticulously

planned, fully prepared, and executed with complete professionalism.

It took eight years before

economic hardship, government corruption, and anger at the nation’s costly

support of foreign proxies of the regime led to another outburst of public

anger and resentment. One notable development marked this episode.

Among the slogans chanted by protesters across the country and reported in the

media were, for the first time: “Bring back the Shah”.

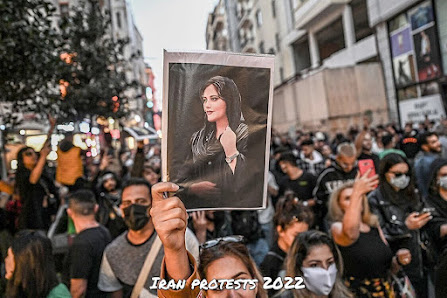

Then on September 13, 2022 Mahsa

Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman, was arrested by Iran’s infamous morality

police. Her nominal offense was that she was wearing her hijab

“improperly”. Mahsa was taken to the Vozara Detention Centre. Three

days later she died.

The Iranian nation erupted in protest.

Thousands took to the streets in cities across the country. Very soon dissent expanded beyond the severe dress code imposed on women and enforced by the morality police. Soon the protesters began targeting the regime itself and the Supreme Leader. Posters with the slogan “Death to the Dictator” began appearing, and videos posted online showed demonstrators burning images of Khamenei and calling for the return of the Pahlavi dynasty.Last month, on May 19, a new wave of protests erupted triggered by widespread anger over poverty, corruption, and economic mismanagement by the regime. They were marked by coordinated actions directly challenging the government’s handling of the economy and social welfare, and demonstrators chanting slogans such as “Death to Khamenei” and “Death to the dictator” were recorded.

The regime’s suppression of these

mass demonstrations was brutal. Security forces confronted protesters

with tear gas and batons. Police, backed by IRGC personnel, used force to

disperse crowds, and in some cases bulldozed protest sites. There were

widespread arrests and a dramatic increase in state executions – at least 175

people were executed during May.

What forces does Pahlavi have at

his beck and call to counter such ruthless suppression? The regular army

remains nationalist and traditionally non-political. He may enjoy quiet

sympathy within it, but there is no visible sign of pro-Pahlavi coordination,

and he seems to have nothing like the infrastructure needed to lead or support

a coup.

The regular police (FARAJA) is

poorly paid and sometimes shows sympathy with protesters, especially in urban

centers, but there is no indication of coordination with external figures like

Pahlavi.

Reformists and pragmatists inside

the Islamic Republic have been marginalized since 2020, but even they do not

associate publicly with Pahlavi. Many fear that aligning with an exiled figure

would mean accusations of treason and possible imprisonment. As far as

the business sector is concerned, those tied to the regime (via IRGC contracts,

bonyads, or patronage) will not defect unless the system is collapsing.

Finally, and perhaps

crucially, Pahlavi’s team has no direct media infrastructure inside the

country. Internet censorship, intimidation, and disinformation severely

limit his ability to organize or communicate with supporters on the ground.

His most effective channels are diaspora satellite stations and social media,

which are limited in reach due to filtering and surveillance.

In short, there is no confirmed underground or internal network working directly for, with, or under Pahlavi. There are grassroots networks inside Iran: feminist, student, labor, and ethnic groups. These movements are fragmented and internally suspicious of external figures, even when monarchism isn’t the issue.

The available

evidence seems to indicate that Reza Pahlavi lacks the internal support

structure and organizational mechanisms required to coordinate a successful

uprising from within. He seems to hope that one will occur, and that he

will be called upon to help develop a democratic government afterwards.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)